Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology

- Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology Chart

- Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology Pdf

- Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology Chart

I have created this page to address a few of the more common nuts-and-bolts questions people have about measuring the Big Five. I have written this page in a fairly informal style, and I have not attempted to be comprehensive. For a fuller treatment of measurement and theoretical issues, I recommend that you look at the 2008 Handbook of Personality chapter by Oliver John, Laura Naumann, and Chris Soto (which is a revision of a 1999 Handbook chapter that Oliver and I wrote, which in turn is a revision of a 1990 chapter by Oliver).

(Note: This page was written to help researchers who want to measure the Big Five as part of their research programs. If you came across this page out of curiosity about your own personality, you can fill out a free questionnaire and get instant, personalized feedback at www.outofservice.com. Two longer versions, offering more detailed feedback, are available from John Johnson’s webpage.)

There are 12 zodiac signs in Western astrology, and each of them has its own character traits. They also each represent an astronomical constellation. Indeed, each sign has a strong influence on your personality, opinions, and emotions. Something that interrupts your plans. When somebody talks about new ideas and theories, you mostly find it. People usually find you. People often appreciate your ability to be. You think that it's more important for children to.

Contents:

The Big Five are five broad factors (dimensions) of personality traits. They are:

- Extraversion (sometimes called Surgency). The broad dimension of Extraversion encompasses such more specific traits as talkative, energetic, and assertive.

- Agreeableness. Includes traits like sympathetic, kind, and affectionate.

- Conscientiousness. Includes traits like organized, thorough, and planful.

- Neuroticism (sometimes reversed and called Emotional Stability). Includes traits like tense, moody, and anxious.

- Openness to Experience (sometimes called Intellect or Intellect/Imagination). Includes traits like having wide interests, and being imaginative and insightful.

- Personality is a stronger predictor of behaviour across all situations but not a strong predictor of an individual’s behaviour at a specific time in a specific situation. Personality traits are the most useful psychological tools that predict behaviour 60 most strongly. 4.3.1 The Behavioural Consistency Controversy Key Issues in Personality.

- One commonly held idea is that greater cognitive ability does not matter or is actually harmful beyond a certain point (sometimes stated as 100 or 120 IQ points). We empirically tested these notions using data from four longitudinal, representative cohort studies comprising 48,558 participants in the United States and United Kingdom from 1957.

As you can see, each of the Big Five factors is quite broad and consists of a range of more specific traits. The Big Five structure was derived from statistical analyses of which traits tend to co-occur in people’s descriptions of themselves or other people. The underlying correlations are probabilistic, and exceptions are possible. For example, talkativeness and assertiveness are both traits associated with Extraversion, but they do not go together by logical necessity: you could imagine somebody that is assertive but not talkative (the “strong, silent type”). However, many studies indicate that people who are talkative are usually also assertive (and vice versa), which is why they go together under the broader Extraversion factor.

For this reason, you should be clear about your research goals when choosing your measures. If you expect that you might need to make finer distinctions (such as between talkativeness and assertiveness), a broad-level Big Five instrument will not be enough. You could use one of the longer inventories that make facet-level distinctions (like the NEO PI-R or the IPIP scales – see below), or you could supplement a shorter inventory (like the Big Five Inventory) with additional scales that measure the specific dimensions that you are interested in.

It is also worth noting that there are many aspects of personality that are not subsumed within the Big Five. The term personality trait has a special meaning in personality psychology that is narrower than the everyday usage of the term. Motivations, emotions, attitudes, abilities, self-concepts, social roles, autobiographical memories, and life stories are just a few of the other “units” that personality psychologists study. Some of these other units may have theoretical or empirical relationships with the Big Five traits, but they are conceptually distinct. For this reason, even a very comprehensive profile of somebody’s personality traits can only be considered a partial description of their personality.

The Big Five are, collectively, a taxonomy of personality trait: a coordinate system that maps which traits go together in people’s descriptions or ratings of one another. The Big Five are an empirically based phenomenon, not a theory of personality. The Big Five factors were discovered through a statistical procedure called factor analysis, which was used to analyze how ratings of various personality traits are correlated in humans. The original derivations relied heavily on American and Western European samples, and researchers are still examining the extent to which the Big Five structure generalizes across cultures.

Some researchers use the label Five-Factor Model instead of “Big Five.” In scientific usage, the word “model” can refer either to a descriptive framework of what has been observed, or to a theoretical explanation of causes and consequences. The Five-Factor Model (i.e., Big Five) is a model in the descriptive sense only. The term “Big Five” was coined by Lew Goldberg and was originally associated with studies of personality traits used in natural language. The term “Five-Factor Model” has been more commonly associated with studies of traits using personality questionnaires. The two research traditions yielded largely consonant models (in fact, this is one of the strengths of the Big Five/Five-Factor Model as a common taxonomy of personality traits), and in current practice the terms are often used interchangeably. A subtle but sometimes important area of disagreement between the lexical and questionnaire approaches is over the definition and interpretation of the fifth factor, called Intellect/Imagination by many lexical researchers and Openness to Experience by many questionnaire researchers. This issue is discussed in the aforementioned chapter.

Five-Factor Theory, formulated by Robert (Jeff) McCrae and Paul Costa (see, for example, their 2008Handbook of Personality chapter), is an explanatory account of the role of the Big Five factors in personality. Five-Factor Theory includes a number of propositions about the nature, origins, and developmental course of personality traits, and about the relation of traits to many of the other personality variables mentioned earlier. Five-Factor Theory presents a biological account of personality traits, in which learning and experience play little if any part in influencing the Big Five.

Five-Factor Theory is not the only theoretical account of the Big Five. Other personality psychologists have proposed that environmental influences, such as social roles, combine and interact with biological influences in shaping personality traits. For example, Brent Roberts has recently advanced an interactionist approach under the name Social Investment Theory.

Finally, it is important to note that the Big Five are used in many areas of psychological research in ways that do not depend on the specific propositions of any one theory. For example, in interpersonal perception research the Big Five are a useful model for organizing people’s perceptions of one another’s personalities. I have argued that the Big Five are best understood as a model of reality-based person perception. In other words, it is a model of what people want to know about one another (Srivastava, 2010).

Regardless of whether you endorse any particular theory of personality traits, it is still quite possible that you will benefit from measuring and thinking about the Big Five in your research.

For an introduction to the conceptual and measurement issues surrounding the Big Five personality factors, a good place to start is the Handbook of Personality chapter by Oliver John, Laura Naumann, and Chris Soto. The chapter covers a number of important issues:

- The scientific origins and history of the Big Five

- Theoretical accounts of the Big Five

- Comparisons of different measurement instruments

The chapter includes a conceptual and empirical comparison of three measurement instruments: Oliver John’s Big Five Inventory (BFI), Paul Costa and Jeff McCrae’s NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), and Lew Goldberg’s set of 100 trait-descriptive adjectives. There is no one-size-fits-all measure, but the chapter includes our recommendations on which instrument(s) you should use for different applications.

The Big Five Inventory (BFI) is a self-report inventory designed to measure the Big Five dimensions. It is quite brief for a multidimensional personality inventory (44 items total), and consists of short phrases with relatively accessible vocabulary. A copy of the BFI, with scoring instructions, is reprinted in the chapter as an appendix (the last 2 pages). It is also available through Oliver John’s lab website. No permission is needed to use the BFI for noncommercial research purposes (see below).

The BFI is not your only option for measuring the Big Five…

The International Personality Item Pool, developed and maintained by Lew Goldberg, has scales constructed to work as analogs to the commercial NEO PI-R and NEO-FFI scales (see below). IPIP scales are 100% public domain – no permission required, ever.

Colin DeYoung and colleagues have published a 100-item measure, called the Big Five Aspect Scales (BFAS), which scores not only the Big Five factors, but also two “aspects” of each. The BFAS is in the public domain as well.

If you want items that are single adjectives, rather than full sentences (like the NEO) or short phrases (like the BFI and IPIP), you have several options. For starters, there is Lew Goldberg’s set of 100 trait-descriptive adjectives (published in Psychological Assessment, 1992). Gerard Saucier reduced this set to 40 Big Five mini-markers that have excellent reliability and validity (Journal of Personality Assessment, 1994). More recently, Saucier has developed new trait marker sets that maximize the orthogonality of the factors (Journal of Research in Personality, 2002). Saucier’s mini-markers are in the public domain.

The NEO PI-R is a 240-item inventory developed by Paul Costa and Jeff McCrae. It measures not only the Big Five, but also six “facets” (subordinate dimensions) of each of the Big Five. The NEO PI-R is a commercial product, controlled by a for-profit corporation that expects people to get permission and, in many cases, pay to use it. Costa and McCrae have also created the NEO-FFI, a 60-item truncated version of the NEO PI-R that only measures the five factors. The NEO-FFI is also commercially controlled.

If you need a super-duper-short measure of the Big Five, you can use the Ten Item Personality Inventory, recently developed by Sam Gosling, Jason Rentfrow, and Bill Swann. But there are substantial measurement tradeoffs associated with using such a short instrument, which are discussed in Gosling et al.’s TIPI article and examined in greater depth in an article by Marcus Crede and colleagues.

See here: Norms for the Big Five Inventory and other personality measures. Though it is probably a better idea to think in terms of “comparison samples” rather than norms.

Disclaimer: I do not claim to speak for anyone else, I am not a lawyer, don’t trust a word I say, do not taunt Happy Fun Ball.

The official answer

Under U.S. copyright law, every written work is automatically copyrighted at the moment of creation. The general rule is that you may not copy and distribute a copyrighted work without permission. However, there are two major exceptions to this rule. The first exception is that if a copyright holder has declared a work to be public domain, then anybody can use it. (This is the case for the International Personality Item Pool as well as for Gerard Saucier’s mini-markers). The second exception is the so-called fair use doctrine. If you are using intellectual property in a way that qualifies as fair use, you do not need to get permission to use it. In fact, fair use means you can use something even if the rights-holder loudly and strenuously objects.

Unfortunately, fair use doctrine in U.S. law is pretty fuzzy. Several factors contribute to whether a particular usage is considered fair use. My personal belief is that noncommercial academic research merits protection under fair use doctrine and the First Amendment. However, quoting from Stanford Law’s excellent site on fair use: “Unfortunately, the only way to get a definitive answer on whether a particular use is a fair use is to have it resolved in federal court.” (chapter 9-b) Caveat scholar.

In addition to general principles of fair use, the American Psychological Association warns that there may be special legal and ethical considerations that apply to psychological tests. A major concern for the APA is that prior exposure to a test may invalidate future responses. For example, this is a significant concern for IQ tests, which are subject to practice effects. Prior exposure is almost certainly less of a problem for self-report personality inventories like Big Five measures. Nevertheless, it is an issue that you should consider when using any psychological test.

The practical answer

As mentioned earlier, the IPIP scales, Saucier’s mini-markers, Gosling’s Ten-Item Personality Inventory, and DeYoung’s Big Five Aspect Scales are all in the public domain and may be used for any purpose with no restrictions. Additionally, the BFI (which is copyrighted by Oliver P. John) is freely available to researchers who wish to use it for noncommercial research purposes. More details are available on Oliver John’s lab website. If you cannot find your questions answered there, you can contact Laura Naumann (naumann@berkeley.edu) for further information.

As for other measures, I have heard anecdotally that you may be more likely to face objections if you try to use instruments published by for-profit testingcorporations than if you use instruments whose rights are held by individual researchers. An objection may not have any merit, but it will be a hassle to deal with anyway, which is probably the point. If you want to use a commercial instrument for academic (noncommercial) purposes, you should either pay for it, get the author’s permission, or be prepared to defend your actions as fair use.

However, many individual researchers I have talked to would be delighted to see their measures used (and cited!) by other scientists, even if the researchers have not declared the measures to be in the public domain. If you are conducting academic research, are not making a profit, and you are not conducting a large-scale data collection (such as a national survey or a public Internet study, which might clash with other such efforts), then it is probably safe to go ahead and use a noncommercial measure without formal permission.

Srivastava, S. ([this year]). Measuring the Big Five Personality Factors. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://psdlab.uoregon.edu/bigfive.html.

Thanks to Lew Goldberg and Jeff McCrae for helpful comments and corrections to this page.

Maybe astrology is mumbo-jumbo or maybe it’s aligning with the spiritual energy of the universe. But does it even matter?

Jun 12, 2019·10 min read

Astrology is the study of patterns and relationships — of planets in motion, our birth chart, synastry with others, the make-up of elements — and using that knowledge as a tool to find meaning. Data science is the field that uses scientific methods, processes, algorithms, and systems to extract knowledge and insights from data.

“I’m a Sagittarius sun, Taurus moon, and a Libra rising… and what is your birth chart?” I would usually say to friends or acquaintances when getting to know someone better. If they aren’t immediately turned off by Astrology, I’ll go into more detail. If they are even more curious, I’ll evaluate their planetary Natal Chart.

My close friends may think I bring up astrology way too often and take it way to seriously… While part of me agrees with them, through the last 4 years I’ve found Astrology to be surprisingly useful.

Here’s how I use Astrology in my daily life:

- Interpret different aspects of mine and peoples’ behavior, natural tendencies, and personalities

- Foster mindfulness, self-awarenasess, and reflection through periodic horoscope readings

- Predict/anticipate energy levels & moods

- Connect me to others and the world

Some think it’s a little silly, even nonsensical. I’ve had people express anger towards me for being someone who utilizes pseudo-science like Astrology for insight and advice. Even I initially thought astrology was absurd.

Astrology argues this: that at the precise moment you separate from the womb and manifest into your own living body, the arrangement of the planetary bodies around you correlate with the aspects of your self. Sounds far out. Hocus-pocus even!

But once I started looking at astrology through the lens of data science, my entire perspective changed. Here’s how.

Data science is an emerging hot career field, synthesizing the power of statistics and modern computer science. For instance, IBM predicts the “demand for data scientists will soar 28% by 2020” with an average pay of $105,000. There’s a lot of talk about data science without any understanding of what it really is. You might not see it at first, but we as human beings are wired to use principles of data science every day.

Data science: statistics on steroids

In order to understand data science, you need to know a little of basic statistics. Actually, we are all practicing statisticians! According to Leo Breiman’s “Statistical Modeling: The Two Cultures”, statistics start with data which is informationyou measure, observe, and feel.

Every second you are alive, your body is processing an enormous amount of data — what you see, feel your emotions, the position of your body, etc — and making sense of it!

Let’s take — for example — birth. When you are born under the celestial heavens and gain consciousness you enter a world that you had no understanding of. You have zero to little data in your hard drive so to speak. So once you breathe your first breath and see your first ray of light you begin to absorb the data around you. Picture yourself back to when you were a newborn baby. Forced into a brand new world with no familiarity with all the data you are taking in. Naturally, you are overwhelmed by the amount of data you are processing so you cry. Mom likely gave you your first meal to shut you up. You’ve been satisfied with mom’s milk. Hours pass, you take a nap, and you wake up start to cry again until Mom feeds you.

A couple more times of crying then feeding, you begin to notice that when you cry, someone like your mom is likely to cater to you — with mom’s touch, attention, and most importantly, food. Eventually, you come to understand this process: that when you input the action of crying, you expect the outcome of being fed by mom.

Congratulations! You have created your very first statistical model!

A statistical model is an algorithmic way to predict what happens in your life. Just like with our first model, our mind has been continuously analyzing the data we receive every day. With each data point, the mind creates more associations between inputs and what we observe. Eventually, we create models that explain the phenomena we experience or the goals we want to achieve. The baby has a model for call for food from its mom: by crying.

Data science takes the predictive modeling ability and creativity of the human brain to make connections and exponentiates the scale and speed through modern computer science and emerging types of digital data.

Changing your model means changing your worldview

We use our own personal models every day to predictably accomplish anything and everything! Here are some examples: going to school, preparing for a test or job, figuring out how much you will spend this weekend, or wooing a potential partner. We have our own personal models on how to likely guarantee success in all of your endeavors. How I prepare for a test is different than yours. Your model for getting dates on Tinder is different than mine as a gay man. Our models for predictably accomplishing what we want are personal and individualized models on our unique life experiences and identities.

But sometimes we don’t get the results we predict from our models. Can’t get an A on any test? Can’t get a date on Tinder? Maybe its not the other people or ourselves who are the problem.

Ideally, we consciously and subconsciously refine and change our models as we evaluate the results of our actions. If our actions produce unfavorable results that don’t agree with the way we see the world, we can change the model and the behavior to produce different results. However, this only happens if we allow our ego to get hurt by admitting we were using the wrong model.

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” — Rita Mae Brown

It’s not easy, but we have to be receptive to the data and make changes accordingly. The aggregate of all of your models of the world and how they interact manifest asyour unique worldview. We use our worldview to do the following:

- Make predictions of what will happen in the world. For example, you may predict which team will win your favorite sport. Or you might predict whether or not mom and dad will get mad at you if you come home past 11 pm or before 11 pm.

- Extract meaning and understanding about the world. We use our worldview to explain why some relationships work while others do not. We justify why homelessness is allowed exists or why people are ultimately good are evil. We observe and interpret data to either challenge or underscore our predominant worldview.

With our predominant worldview in the face of new data, we choose to accept it as truth to challenge our assumptions and adjust our worldview or ignore it and remain blissfully ignorant.

“all models are wrong, but some are useful” — George Box

Every day we are using our particular worldview to navigate our world. Ultimately, our human understanding of the world will always be a simplification of reality. In other words, what you know and how you know it is ultimately wrong.

You may have a basic understanding of how gravity works: you know enough about it not to jump from high heights. But do you understand the science behind law of gravity: why matter attracts other matter?

However much we learn and understand, our models of anything will be by human-nature, incomplete and wrong.

Despite being all wrong, the models within our worldview help us survive. Even though you do not fully understand gravity — for example — you still know enough not to jump off a cliff because your model will predict that you have a high possibility of dying. Our wrong models are still useful.

Our models can vary by 1) predictive power and 2) ease of interpretation. The best models are usually both highly predictive and understandable. In other words, our worldview correctly explains the phenomena we observe, and we have an intuitive way of understanding the relationship between the input variables and the results.

Despite being useful for accomplishing our goals throughout the day there is inherently always a degree of bias and imperfection in our models: they only capture a portion of the truth. As we refine our models in life and across generations we get closer and closer to the real truth.

If we listen to the data, our worldview can become more refined, nuanced, and closer to the truth.

We also have models for predicting and explaining our behavior and personality. Some companies use the models in their leadership development and communication pieces of training. Others casually use models to predict love compatibility or describe a person’s personality.

If you’ve ever taken a psychology course, you might be familiar with the Myers-Briggs Personality Test, which categorizes you with a four-letter acronym (ie. ENTJ, INFP, etc.). Most of these models are 1) somewhat predictive, and 2) easy to understand. The tests ask you to input responses to a variety of behavioral questions and an algorithm calculates a specific personality profile according to the model you use.

I’ve listed my results for several famous behavioral models below:

Valuing utility over understanding

Most behavioral models tend to value simple, understandable models. When I get my results, they really make sense with how I answered the questions. Taking the Myers-Briggs for example, I got extroverted because I answered in favor of extroversion in the test.

Something like Astrology, however, is completely non-intuitive — the inputs for the model are the exact time and location that you are born and the output is your astrological natal chart with a framework that assess’s your personality and provides periodic predictions for how you may act or interact with others.

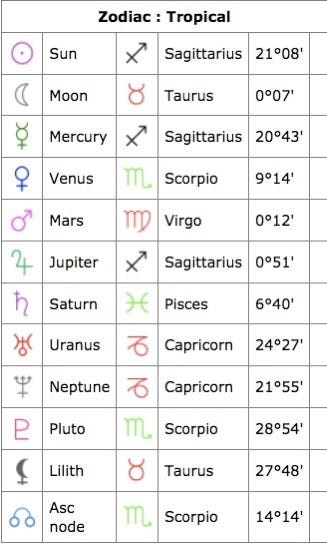

All of these predictions are determined by which zodiac each planet was residing in at your time of birth. Each planet corresponds to a different facet of your self. My natal chart for example predicts that my outward self is adventurous and zealous for truth while my emotional self can be stubborn and jealous.

This interpretation is derived from the fact that the Sun and Moon were residing in the Sagittarius and Taurus in the sky when I was born.

Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology Chart

So between Myers-Briggs’s and Astrology or any other personality model, which one do you use? The answer lies in your personal values and the assumption that all models are wrong, but some are useful.

For me, I decide to use whichever model seems the most useful for the situation. At work, I rely on the DISC or Strengthfinders to help navigate my relationship with others. Generally, however I like Astrology for reflection, assessment, and spiritual connection with myself, others, and the world.

At the end of the day, I am not here to argue that astrology is right any more than Myers-Briggs, Strengthfinders, etc. After all — every model is wrong — so we have to be critical of the models we are using to interpret the world.

I am just one 24-year-old human of billions of humans on this planet. It would be arrogant to think with 100% certainty that astrology is infallible. I do not have the scientific explanation for why humanity communes and connects with the heavenly bodies.

But scientific worldview transforms all the time. From a flat to a spherical earth, or explanation of evolution, and even now, discovering the importance of the bacterial microbiome that controls and affects our mood, behavior health. So who knows!

Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology Pdf

Maybe in the future scientists will discover electromagnetic links between us and the other planets in the same way that we sync with the moon’s lunar cycles or the sun’s circadian rhythm. Maybe we will uncover the reason we feel connected and alone, important yet insignificant when we look up to the heavens.

But for now, I’ll continue to use whatever tools I have in my tool-belt to try and navigate this world. And if the tools stop working, if I’m no longer receiving the results I expect, I’ll choose another tool, another model, another worldview. I’ll live each day with the understanding that in an instant my whole perspective can shift. I’ll look up to the heavens, thank God I’m alive and give gratitude to the Universe for another day to discover more truth.

My name’s Kevin. I’m trying to find more ways to progress interesting ideas forward and writing is a new way I’m doing that.

I like to think about how we can design living, learning, and working communities that optimize how people learn and actualize their potential. Let’s talk on Twitter.

References

Does Dating Site Personality Data Point To Truth In Astrology Chart

- Breiman, Leo. Statistical Modeling: The Two Cultures (with comments and a rejoinder by the author). Statist. Sci. 16 (2001), no. 3, 199 — 231. doi:10.1214/ss/1009213726. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.ss/1009213726

- Columbus, Louis. “IBM Predicts Demand For Data Scientists Will Soar 28% By 2020.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 14 May 2017, www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2017/05/13/ibm-predicts-demand-for-data-scientists-will-soar-28-by-2020/.

- Stephens-Davidowitz, Seth, and Steven Pinker. Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Reveals about Who We Really Are. Dey St./William Morrow, 2018.

- Nicholas, Chani. “Horoscopes.” Chani Nicholas, 2 June 2019, chaninicholas.com/horoscopes/.

- Stewart, Benjamin, director. Kymatica. Kymatica, YouTube , youtu.be/14Bn3uYqaXA.